Is your soil really alive, or is it just inert material? The answer lies not in what you see, but in what you cannot see. Most people learn about mycorrhizal fungi as nutrient exchangers. Phosphorus in exchange for carbon. Roots feed fungi, fungi feed plants. That story is true, but incomplete. What lies beyond it is far more fascinating and far more important for how soils actually function. Beneath every healthy plant exists an invisible transport network, built not for roots alone, but for microbes.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi do not just connect plants to nutrients. They create living corridors that allow bacteria to move, organize, interact, and evolve. This dynamic zone is known as the mycorrhizal hyphosphere. Understanding what happens here changes how we see soil, microbes, and plant health altogether.

You may notice this article feels a bit more technical than my usual writing. That is intentional. Some soil processes need a closer look, because understanding them properly can make a real difference in how we manage soil and how much our fields can produce.

The mycorrhizal hyphosphere: A living corridor in a sea of soil

So, what is this critical zone? The mycorrhizal hyphosphere is the microscopic ecosystem that surrounds the thread-like filaments (hyphae) of mycorrhizal fungi. It’s a world apart from the bulk soil. Imagine the difference between a barren desert and a lush, protected riverbank. The hyphosphere is that riverbank:

- Hydrated: Fungal hyphae maintain a thin film of water, creating an oasis during drought.

- Nourished: It’s rich in carbon compounds exuded by roots and fungi, the currency of the soil economy.

- Structured: Hyphae form a physical scaffold, a living architecture.

- Crowded: Microbial life here is up to 1,000 times denser than in the surrounding soil.

This isn’t just a habitat; it’s a biologically engineered transport and communication system. The fungi are the architects, building the infrastructure. The bacteria are the active citizens, moving, trading, and cooperating. This is the vibrant proof that soil is alive.

This living network is part of what gives soil its “memory” and identity. When it’s damaged, the whole system suffers. Learn about this concept in 7 amazing secrets your soil remembers that will transform farming.

Bacterial movement: The pulse of a living system

A dead substrate is static. A living system is in motion. One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for living soil is the incredible, strategic bacterial movement within the mycorrhizal hyphosphere. Bacteria aren’t passive prisoners in soil; they’re savvy navigators.

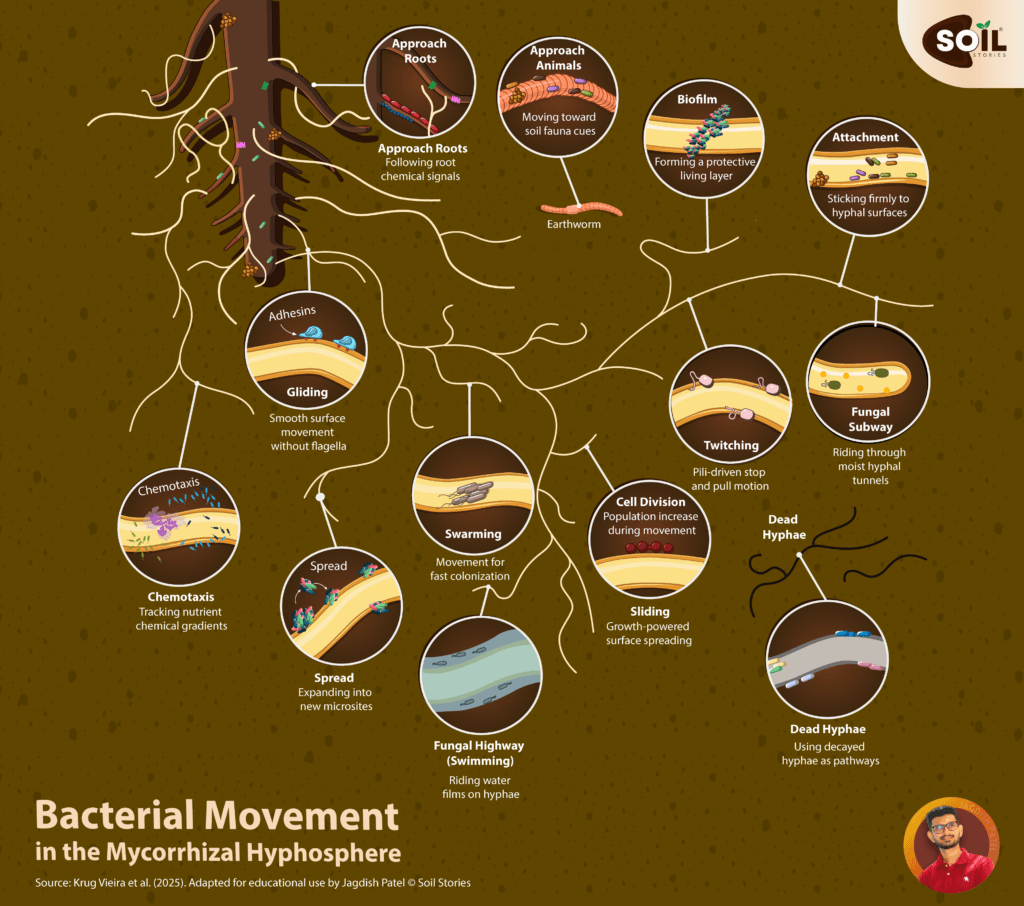

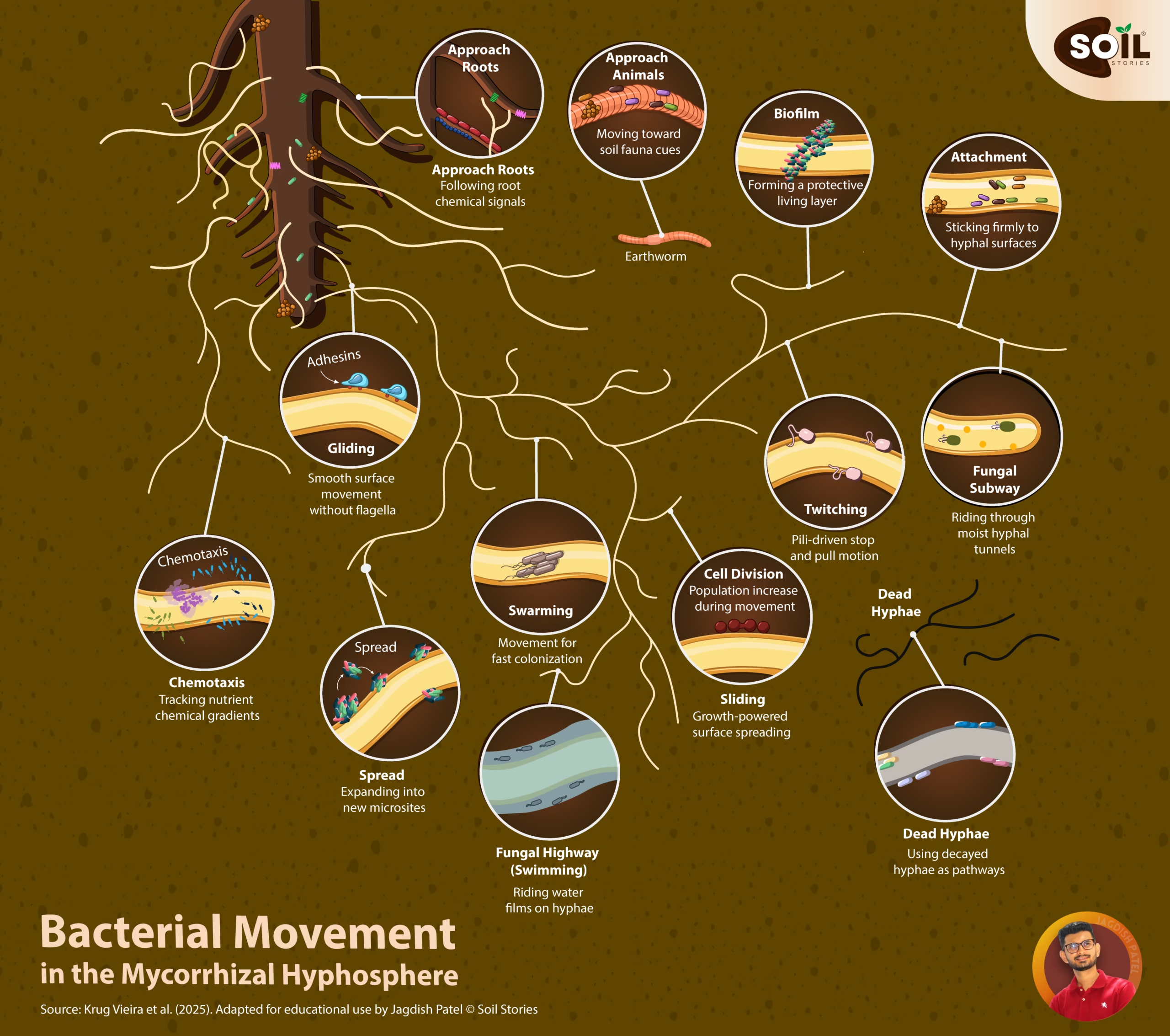

They use sophisticated methods to travel the fungal highways:

- Chemotaxis: Following scent trails of nutrients, like bloodhounds tracking a smell.

- Gliding: Smoothly creeping along the fungal “roads.”

- Surfing: Some bacteria, like Pseudomonas, can literally ride the pressure waves emitted from the tips of growing hyphae.

- Swarming: Moving as coordinated armies to colonize new roots.

This mobility solves the biggest problem in soil: distance. A millimeter in soil is a vast, fragmented canyon to a microbe. The mycorrhizal hyphosphere collapses this space, turning isolated pockets into connected neighborhoods. This constant, purposeful movement is the pulse of the living soil.

The fungal internet: More than just nutrient trade

For too long, the story ended with “fungi trade phosphorus for carbon.” The mycorrhizal hyphosphere reveals a far grander narrative. Mycorrhizal fungi aren’t simple traders; they’re ecosystem engineers. They build the fungal internet, a mycelial network that does much more than shuttle nutrients.

A strange fact: This network is so extensive that a single cubic meter of healthy soil can contain over 1,000 kilometersof fungal hyphae. That’s enough to stretch across a small country, all packed beneath your feet, facilitating microbial traffic.

This infrastructure enables functions that define a living system:

- Rapid communication: Stress signals from a plant under insect attack can be transmitted through the network to neighboring plants, priming their defenses.

- Resource redistribution: Nutrients can be shuttled from dying plants to seedlings, or from areas of plenty to areas of lack, acting as a communal support system.

- Microbial governance: The fungi influence which bacteria thrive, essentially “curating” the microbiome for optimal function.

The Food and Agriculture Organization states that soil biodiversity is the “silent, affordable powerhouse” that underpins food production. Their work emphasizes protecting these very networks. Explore their resources on the International Initiative for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Soil Biodiversity.

The hyphosphere effect: Evidence in soil function

How does this microscopic life translate to tangible, observable soil health? The activity within the mycorrhizal hyphosphere directly creates the properties we associate with fertile, “living” soil.

| Observable soil trait | How the mycorrhizal hyphosphere creates it |

|---|---|

| Sweet, earthy smell | Released by actinobacteria (like Streptomyces) thriving in the hyphosphere as they break down organic matter. |

| Crumbly, stable structure | Fungal glue (glomalin) and bacterial biofilms bind particles into water-stable aggregates. |

| Rapid water infiltration | These aggregates create pores, allowing water to enter quickly instead of running off. |

| Slow release of fertility | Microbial necromass (dead microbes) from the hyphosphere is a primary source of stable organic nitrogen. |

| Disease suppression | Biofilms on hyphae physically block pathogens, and beneficial bacteria outcompete them. |

Strange fact: The “forest smell” after rain, called petrichor, is partly caused by geosmin, a compound produced by Streptomyces bacteria in the soil. This iconic scent is literally the breath of a living soil microbiome, often concentrated in active hyphospheres.

The ultimate proof: Evolution at high speed

Inert things don’t evolve; living systems do. Perhaps the most profound evidence from the mycorrhizal hyphosphere is its role as an evolutionary accelerator. By forcing diverse bacteria into intimate contact within biofilms, it becomes a hotspot for horizontal gene transfer (HGT).

Think of it as a microscopic innovation district. Genes for antibiotic resistance, novel enzyme production, or stress tolerance are swapped between species at rates up to 1,000 times faster than in isolated soil. When a challenge like a new toxin or drought arises, the hyphosphere community can rapidly “remix” its genetic toolkit to adapt. This dynamic, responsive evolution is a hallmark of life, and it’s happening constantly in the soil beneath us.

This community is the hidden engine of a functioning farm. Discover its broad roles in soil microbes: the hidden engine of sustainable farming.

How to listen to what your soil is telling you

If the mycorrhizal hyphosphere is the proof of life, how do we nurture it? You can’t see it directly, but you can observe the results of its activity.

Signs of a living soil (active hyphosphere):

- Earthworms and abundant soil insects.

- A crumbly structure that holds together when squeezed but breaks apart easily.

- Quick drainage after heavy rain, with no pooling or crusting.

- Old roots are matted with soil that won’t shake off (a sign of hyphal attachment).

- A sweet, earthy aroma.

Signs of a dying or dead soil (damaged hyphosphere):

- Compacted, hard, or dusty structure.

- Water pools or runs off quickly.

- Requires increasing amounts of fertilizer for the same yield.

- Has a sour, metallic, or chemical odor.

Actions to foster the hyphosphere:

- Feed the network: Use diverse cover crops and organic amendments (compost) to provide a steady, complex food source.

- Stop the violence: Minimize tillage and chemical fungicides/fertilizers that destroy fungal networks.

- Keep it covered: Maintain plant cover or mulch to moderate temperature and moisture, creating ideal conditions for hyphal growth.

- Inoculate thoughtfully: In degraded soils, consider applying mycorrhizal inoculants that contain both fungi and their bacterial partners to kickstart the system.

Conclusion: The verdict on living soil

So, is your soil really alive? The evidence from the mycorrhizal hyphosphere leaves little doubt. Constant bacterial movement, intricate communication, collaborative biological engineering, and rapid adaptation are not traits of dead material. They are the signatures of a vibrant, complex living system quietly shaping everything above it.

For me, the mycorrhizal hyphosphere represents a shift in how soil should be understood. It reminds us that soil is not something we improve simply by adding inputs. It is something we learn to work with. When we move from treating soil as a chemical warehouse to supporting it as a living ecosystem, we unlock resilience, fertility, and stability that no single practice or product can provide.

Understanding this hidden world has changed how I see soil forever. And once you begin to notice the quiet activity beneath your feet, the way soil connects life, movement, and balance, it becomes difficult to see soil as anything other than alive.

Explore more on the living soil:

Is your soil really alive? The mycorrhizal hyphosphere tells the truth

Is your soil really alive, or is it just inert material? The answer lies not…

World Soil Day special: 7 amazing secrets your soil remembers that will transform farming

December 5th, 2025 marks another World Soil Day but this year, we’re uncovering the hidden…

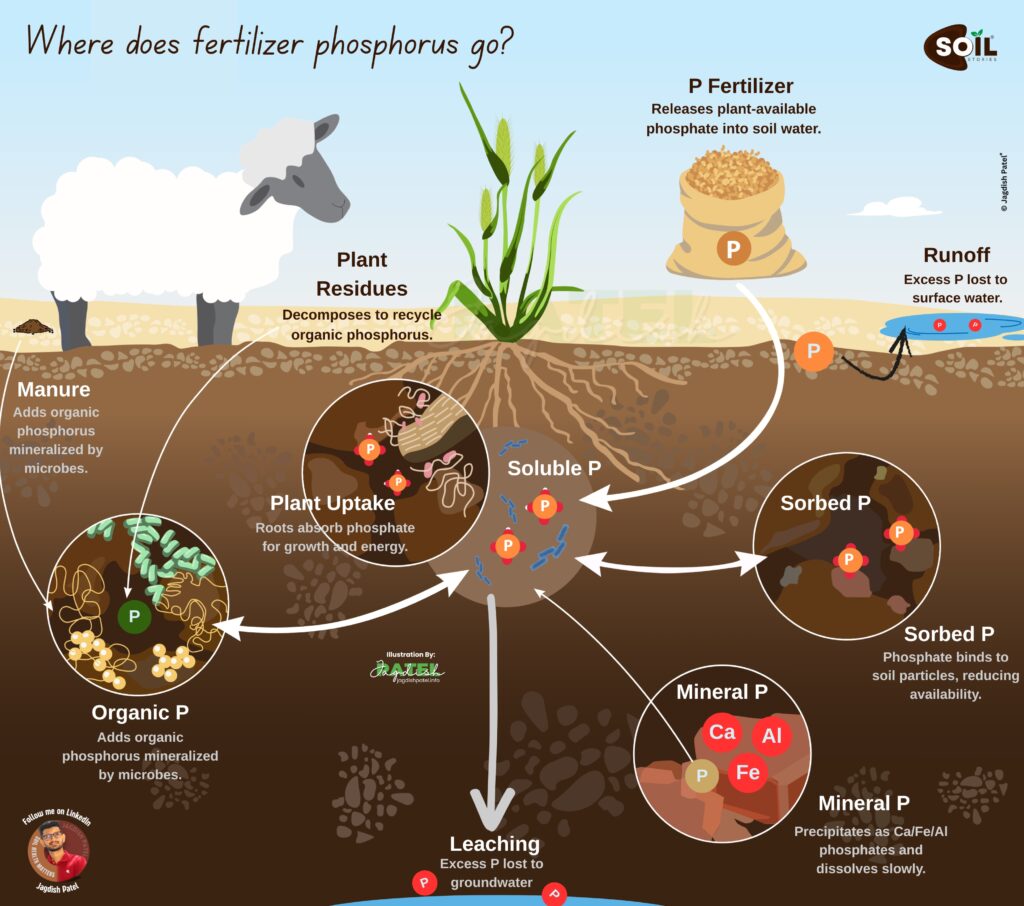

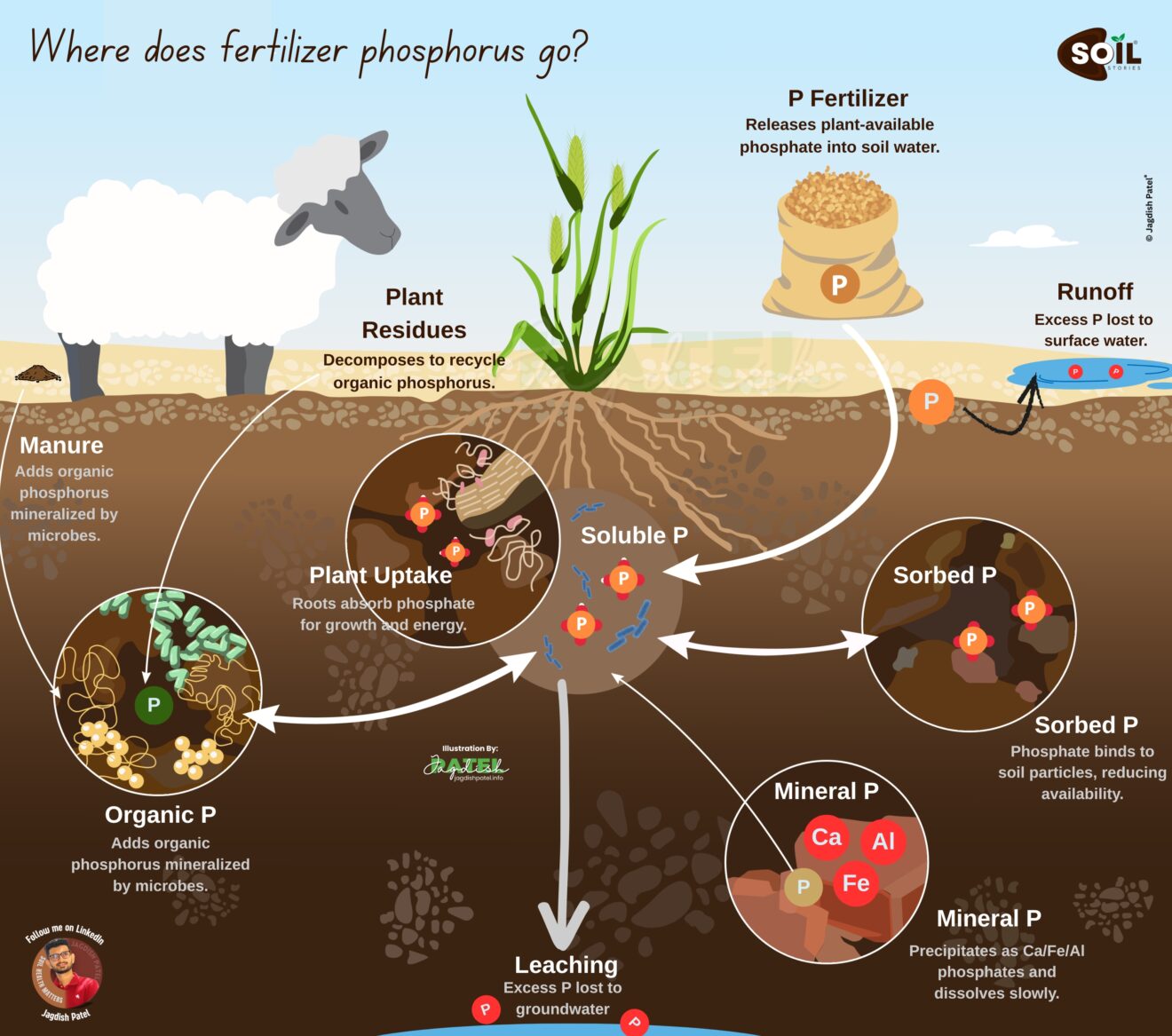

Fertilizer Phosphorus Management Guide: Why Crops Don’t Get Phosphorus and How to Fix It

Fertilizer phosphorus management is one of agriculture’s biggest hidden challenges. Farmers spend billions annually on phosphorus…

The Hidden Network That Feeds 7.8 Billion People Every Day (And We’re Destroying It)

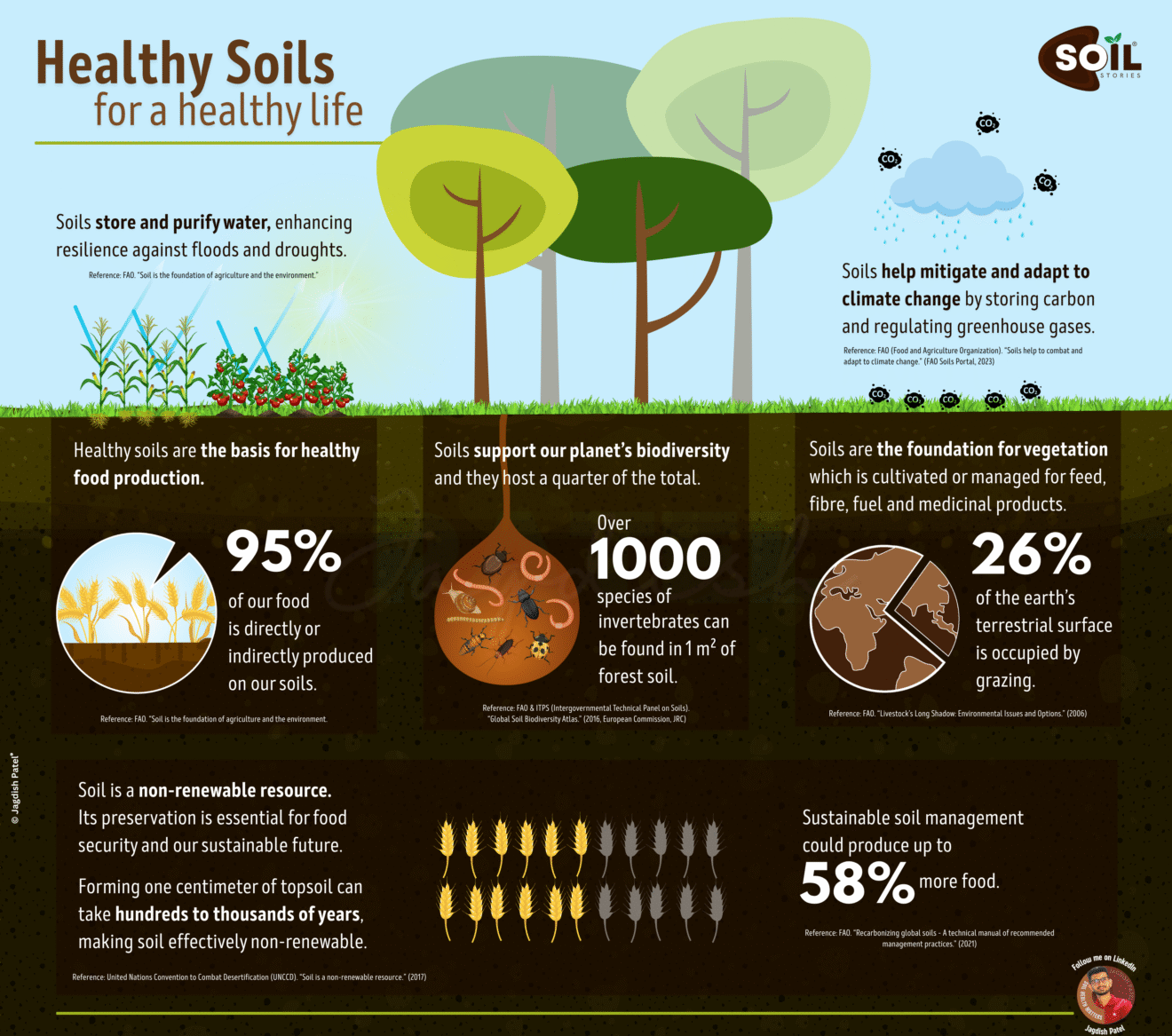

What if the most biodiverse ecosystem on Earth isn’t the Amazon rainforest or a coral…

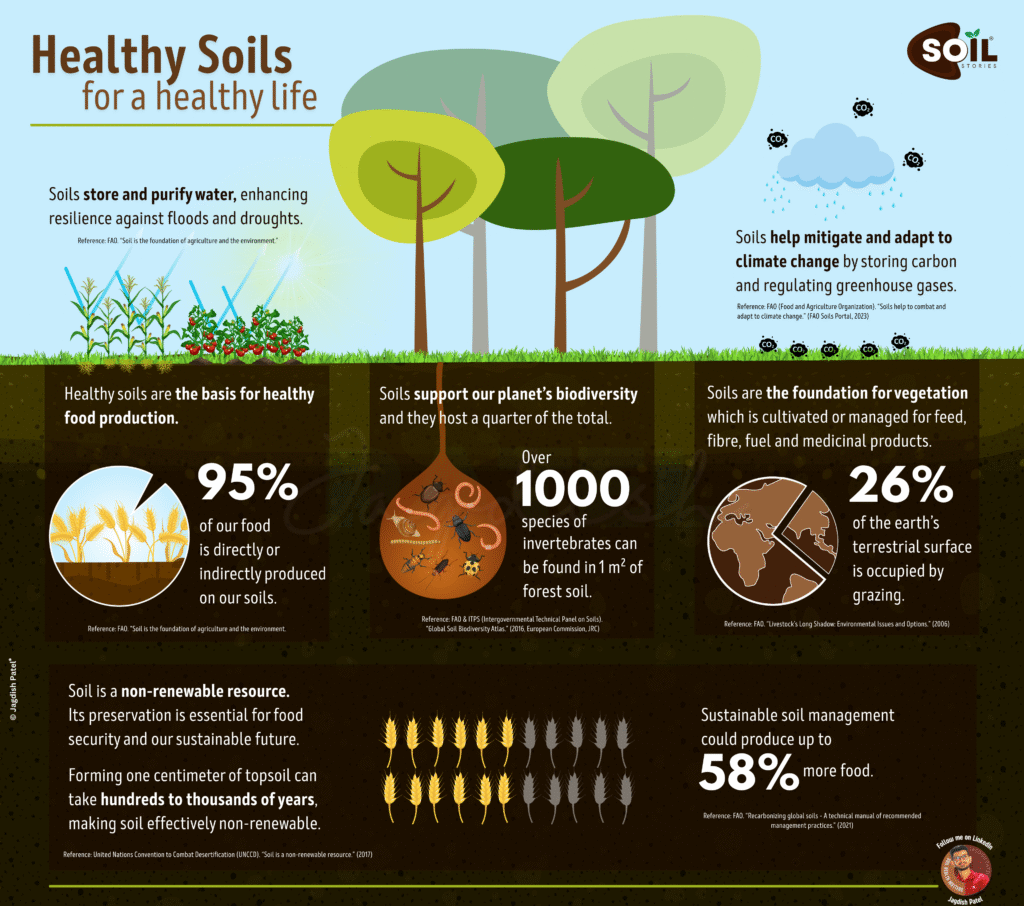

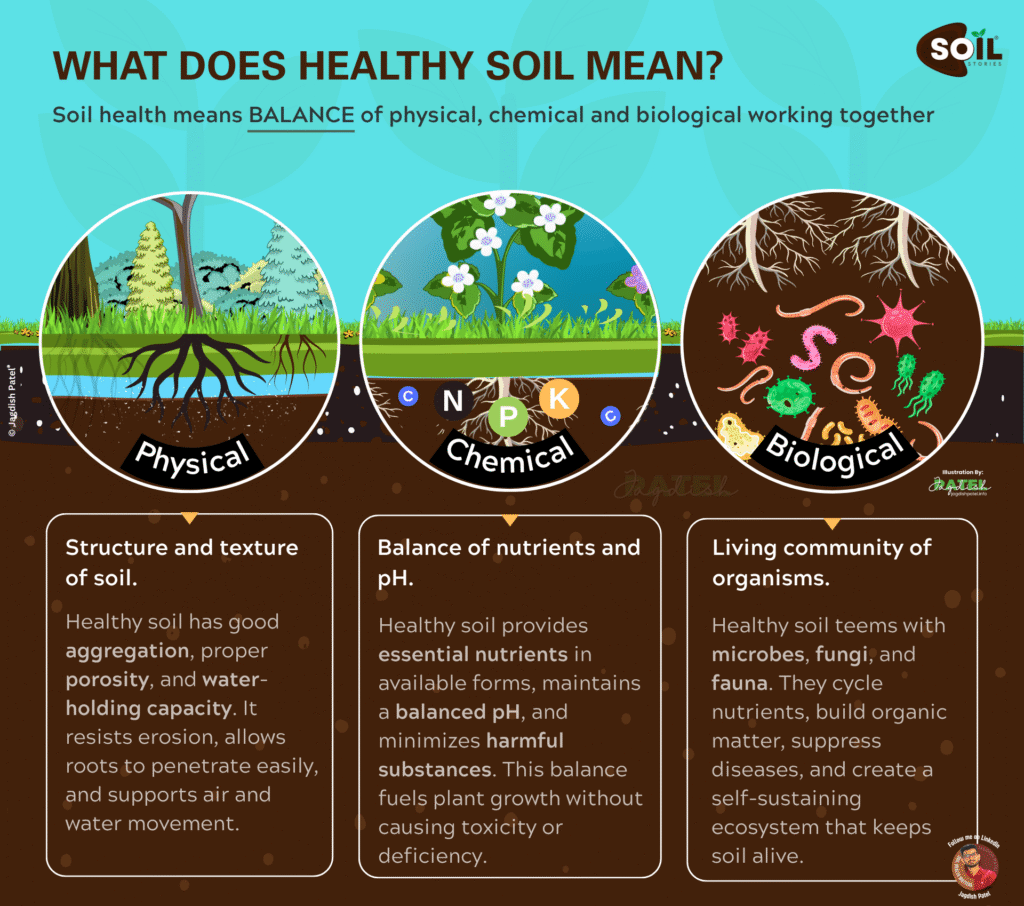

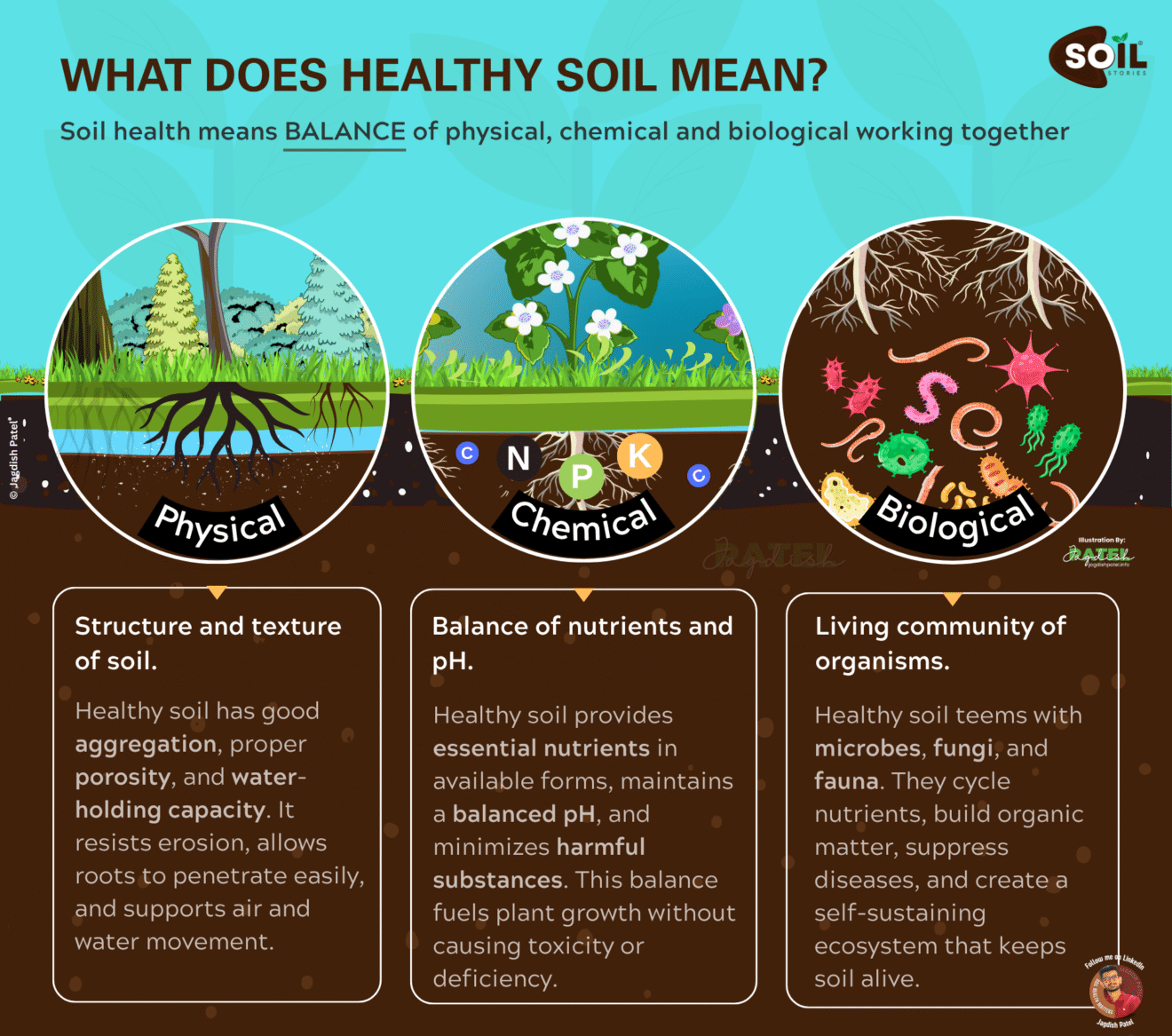

Ultimate Guide to Healthy Soil: 7 Powerful Secrets That Transform Your Garden Forever

What does healthy soil mean for your garden’s success? If you’ve ever wondered why some…

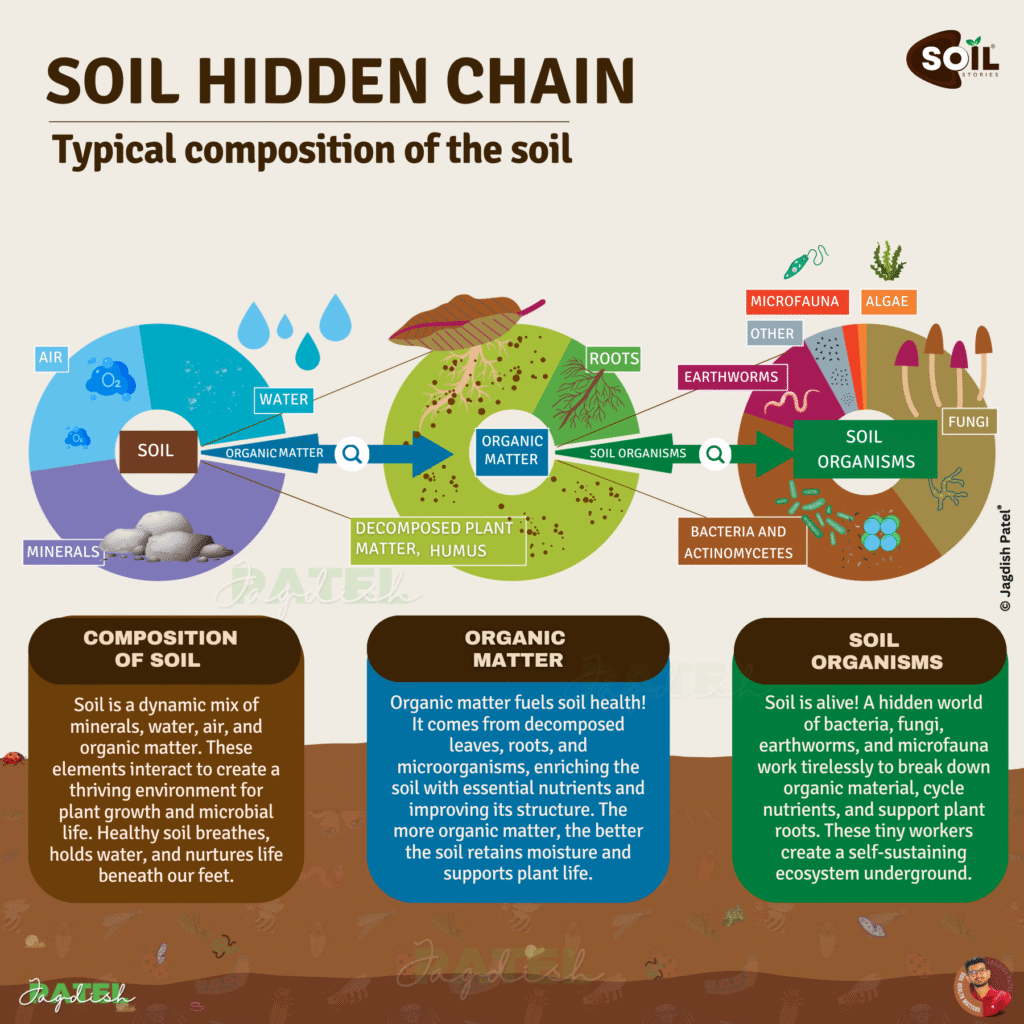

The Living Soil : A bond of Soil, Organic Matter, and Organisms

The living soil is far more than just a substratum for plant growth; it is a…